Chapter 7: Templating

Notice: The Gitbook version of this book has many formatting errors on this page. It appears that the system they are using is actually trying to parse some of the template syntax in inline code samples. For now, if you’re trying to read this online, try reading this chapter on GitHub instead.

Okay, so we know how to tell Kitura to output plain text, and we know how to tell Kitura to output JSON and XML. What about good ol’ classic web pages made with HTML?

Well, since HTML pages are based in plain text, we could do some silly things like…

response.send("<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><title>My awesome web page!</title></head><body><p>…")

But Kitura Template Engine gives us a better way.

Kitura Template Engine and Stencil

A templating engine allows us to build web pages using templates, which are basically like HTML pages with “holes” in them where data from our web application can be plugged into. Here’s a (simplified) example of a template that we’ll be using later in this chapter. Can you see what the output of this is likely to be?

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Title</th>

<th>Artist</th>

<th>Album</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

{% for track in tracks %}

<tr>

<td>{{ track.name }}</td>

<td>{{ track.composer|default:"(unknown)" }}</td>

<td>{{ track.album }}</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}

</tbody>

</table>

Just as the Swift Kuery project was a protocol upon which implementations like Swift-Kuery-MySQL and Swift-Kuery-PostgreSQL could be implemented, the Kitura Template Engine project is a protocol upon which specific templating engines could be implemented. As of this writing, the IBM@Swift project has three implementations available; Mustache, Stencil, and Markdown. We’ll ignore the Markdown implementation as it’s not a complete templating engine in my opinion, and Stencil seems to be more widely used than Mustache in the Swift ecosystem, so we’ll work with the Stencil implementation here.

Stencil is a templating engine inspired by the one provided for Django, a popular web framework for the Python language. It has a pretty good balance of simplicity and advanced features.

For this chapter, we’re going to continue to use the project we used for the previous two chapters. Go ahead and crack open its Package.swift file and add Kitura-StencilTemplateEngine to your project.

Getting Started

Unfortunately, Kitura-TemplateEngine is severely under-documented at the moment. But that’s part of the reason this book exists.

For this chapter, we’ll continue to tinker with our Kuery project. First, we’ll create our template file. Create a new directory at the top level of your project and name it “Views” (with a capital V). Inside that, create a new file, name it hello.stencil, and put the following in there.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello!</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>

Hello, {{ name }}!

</p>

</body>

</html>

Now go into main.swift and add the following to your list of imports:

import KituraStencil

Right after you initialize router, add:

router.setDefault(templateEngine: StencilTemplateEngine())

Finally, let’s create a new route handler.

router.get("/hello/:name") { request, response, next in

response.headers["Content-Type"] = "text/html; charset=utf-8"

let name = request.parameters["name"] as Any

try response.render("hello", context: ["name": name])

next()

}

Now visit “/hello/(your name)” in your browser (so, “/hello/Nocturnal” in my case), and you should see that the page now says “Hello, (your name)!”

Okay, let’s look at what we built here. Let’s start with the hello.stencil file. You probably recognize it as a straightforward HTML file, except for this part:

Hello, {{ name }}!

So this is special Stencil mark-up. Namely, the double-curly-braces, {{ }}, specify that the part in between the pairs of braces will be a variable name, and we want Stencil to insert the value of the named variable into the template at that spot. And the name of that variable is name. We’ll get back to Stencil variables in a bit.

Back in main.swift, we added:

router.setDefault(templateEngine: StencilTemplateEngine())

This basically sets up our instance of Router that when we call its render() method later, it should use an instance of StencilTemplateEngine to render the template. Don’t worry about that too much.

Now let’s look at our new route handler, specifically the last two lines.

let name = request.parameters["name"] as Any

try response.render("hello", context: ["name": name])

So the render() method here takes two parameters. The first is a reference to the template we want to be used; in this simplest case, it’s the same as the filename of the template we created earlier (hello.stencil), minus the extension. The second parameter is a [String: Any] dictionary. That’s why we cast name as an Any before we put it in the dictionary, even though it’s really a String?. Other types we can use in this dictionary include other scalar types such as Int as well as collection types such as Array or Dictionary. We’ll see more examples of this later.

Filters

Stencil allows variables to have “filters” applied to them. There are a number of filters included with Stencil, as well as the ability to implement your own. I’ll show you how they work by showing you how to use default, the most useful filter.

First, go back to your route handler we created previously and change the route path as follows:

router.get("/hello/:name?") { request, response, next in

Do you see the difference? There’s a question mark after the :name. That means that the name parameter is optional in this path, and that the route handler will still fire even if that parameter isn’t included in the given path; in other words, the handler will fire both for “/hello/(your name)” and simply “/hello”.

So rebuild your project and try accessing just the “/hello” path. You should see a page which awkwardly says “Hello, !” You can probably guessed what happened; since there was no name parameter, the String? that Stencil eventually got handed for its name variable had a nil value, so it just rendered nothing in its place.

To fix this, we’ll go back to hello.stencil and tell it to use the default filter. We tell Stencil to apply a filter to a variable by putting a pipe followed by a filter name right after the variable name. In this case we also need to pass in a default value. That default value will be used when the filtered variable is nil. Let’s use “World” as our default value. So go back to hello.stencil and modify the line with the variable to match the following.

Hello, {{ name|default: "World" }}!

Now switch back to your browser and reload the page, and it will now show “Hello, World!” for the “/hello” path, but still properly drop in your name if you visit “/hello/(your name)”.

Blocks

Next, let’s look at Blocks, a method by which we can reduce replication in our Stencil templates. Imagine that your web site will have a largely consistent design from page to page, but the title and body of the page will change from page to page. Well, just as we can fill in parts of a page with variables, we can also fill in parts of a page with other parts of a page using Blocks.

An example should clarify things here. Inside that Views directory you created earlier, create a file named layout.stencil and fill it in as follows.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>My Music Collection: {% block pageTitle %}Oops - no title!{% endblock %}</title>

</head>

<body>

{% block pageContent %}Oops - no content!{% endblock %}

</body>

</html>

Now go back to hello.stencil and let’s change things up a bit.

{% extends "layout.stencil" %}

{% block pageTitle %}Hello!{% endblock %}

{% block pageContent %}

<p>

Hello, {{ name|default:"World" }}!

</p>

{% endblock %}

Build and run. (Note we didn't make any changes to the Swift code here; just the templates.) When visiting the “/hello” and “/hello/(your name)” routes, you should see that the output is pretty much the same as it was before. So what changed under the hood?

Well, in layout.stencil, we defined two blocks named pageTitle and pageContent. A block begins with {% block blockName %} and ends with {% endblock %}. Inside each block, we gave a little bit of placeholder content (the “Oops” messages), but that content will only be visible if those blocks aren't given new content by a child template.

hello.stencil became such a child template when we added the {% extends "layout.stencil" %} directive at the top. Stencil will now pull in and render layout.stencil, but will override the blocks therein with blocks we define in this file. We then go on to define pageTitle and pageContent blocks which get dropped into place of the respective blocks in the parent template.

How is this any better than what we initially had? Because it reduces duplication. Let’s say that in addition to our “/hello” route, we also had a “/goodbye” route which worked similarly. We could then create a goodbye.stencil template that looks like this:

{% extends "layout.stencil" %}

{% block pageTitle %}Goodbye!{% endblock %}

{% block pageContent %}

<p>

Goodbye, {{ name|default:"Everyone" }}!

</p>

{% endblock %}

…And maybe we also had “/good-afternoon” and “/happy-birthday” routes, with corresponding templates. Now we decide that the page looks too plain, so we want to add a CSS file to our pages. We can simply do it by editing layout.stencil:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/styles.css" />

<title>My Music Collection: {% block pageTitle %}Oops - no title!{% endblock %}</title>

</head>

[…]

And that’s it - the changes will be reflected across every route on our site that uses that parent template. On the other hand, if we still had entirely separate templates for each separate route, we would have to edit every template file to add our stylesheet to each one.

Sanitation and Sanity

In case you missed it, this book contains a section at the beginning warning that many of the examples in this book contain security issues which are not fixed due to simplicity’s sake. Well, let’s address that a bit now.

The page for the “/hello” route in its current state has a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability. It takes a value directly from the request URL and prints it back to the page. That means that the user could craft a naughty URL which contains some JavaScript code which then gets executed by a user’s browser.

Try this out by going to “/hello/%3Cscript%3Ealert('oh%20no');%3C%2Fscript%3E”. That last part is the URL-encoded equivalent of <script>alert('oh no');</script>. The resultant HTML code will contain:

<p>

Hello, <script>alert('oh no');</script>!

</p>

So after visiting this URL, your browser will execute the script in the <script> tags and show an alert box with the text “oh no” in it. (Well, maybe. The current version of Safari actually detects what is going on and refuses to execute the script. Things still work in the current version of Firefox, however.) Now the code in this particular example is perfectly benign, but if this example works, then more malicious ones will work, too.

This bugs me, and I’ve raised an issue to propose a fix to make Kitura Template Engine more secure by default. In the meantime, let’s do a little tweaking to fix this problem. Create a new file in your project and name it String+webSanitize.swift, and put in the following.

extension String {

func webSanitize() -> String {

let entities = [

("&", "&"),

("<", "<"),

(">", ">"),

("\"", """),

("'", "'"),

]

var string = self

for (from, to) in entities {

string = string.replacingOccurrences(of: from, with: to)

}

return string

}

}

This is an extension - a way to add methods to classes, in this case the String class, without fully subclassing them. Subclassing is not possible in many cases due to access restriction levels (see the Access Control section in The Swift Programming Language for more on that), and in other cases it may be possible but still undesirable as code you want to interact with (in this case, Kitura) will still expect to see things using the base class. The filename of String+webSanitize.swift matches the “standard” (such as it is) pattern for Swift code files that have extensions in them; namely, BaseClassName+AddedFunctionality.swift.

At any rate, let’s tweak our route handler to use a sanitized string.

router.get("/hello/:name?") { request, response, next in

response.headers["Content-Type"] = "text/html; charset=utf-8"

let name = request.parameters["name"]

let context: [String: Any] = ["name": name?.webSanitize() as Any]

try response.render("hello", context: context)

next()

}

And now try loading the page with the naughty path again, “/hello/%3Cscript%3Ealert('oh%20no');%3C%2Fscript%3E”. Note that you won’t see the alert box anymore, and the page markup will have the following:

<p>

Hello, <script>alert('oh no');</script>!

</p>

Ah, much better. All right, I think you get the idea of how Stencil works. Let’s move on to put it to practical use in our music database app.

The Song List in HTML

Check back to the “/songs/:letter” route handler in your Kuery project. Right now it outputs JSON or XML responses as requested. We’re going to tweak it so it can output an HTML page as well.

Let’s start by creating a template. Add a songs.stencil file and put in the following.

{% extends "layout.stencil" %}

{% block pageTitle %}Songs that start with {{ letter }}{% endblock %}

{% block pageContent %}

<h2>These are songs in my collection that start with the letter {{ letter }}.</h2>

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Title</th>

<th>Artist</th>

<th>Album</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

{% for track in tracks %}

<tr>

<td>{{ track.name }}</td>

<td>{{ track.composer|default:"(unknown)" }}</td>

<td>{{ track.album }}</td>

</tr>

{% empty %}

<tr>

<td colspan="3">

There are no songs that begin with {{ letter }}.

</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}

</tbody>

</table>

{% endblock %}

Oh, hey, new syntax! Yes, we can use for loops in Stencil templates to iterate through arrays; it works pretty much as expected. But there’s also that {% empty %} bit. That part will be shown if the array we’re trying to iterate over has no elements. More on that later.

So that’s the template part. Let’s go back to our Swift code and add the logic to render the template. I’ll just include the relevant part of the switch block.

switch request.accepts(types: ["text/json", "text/xml", "text/html"]) {

case "text/json"?:

[same as before…]

case "text/xml"?:

[same as before…]

case "text/html"?:

response.headers["Content-Type"] = "text/html; charset=utf-8"

var sanitized: [[String: String?]] = []

for track in tracks {

sanitized.append([

"name": track.name.webSanitize(),

"composer": track.composer?.webSanitize(),

"album": track.albumTitle.webSanitize()

])

}

let context = ["letter": letter as Any, "tracks": sanitized as Any]

try! response.render("songs", context: context)

default:

[same as before…]

}

}

Note that we added “text/html” to the array we send to request.accepts(). Also note that we’re using our new webSanitize() method on the values we want to display. (Strictly speaking, we should do this for the XML output as well, since what this method encodes are actually reserved characters for the XML specification, but I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.)

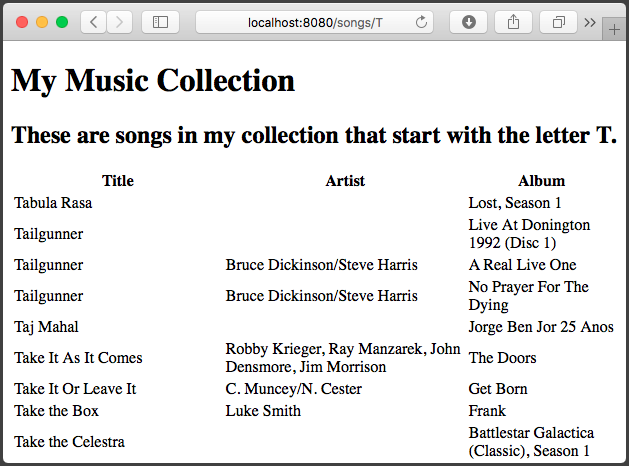

Now go back to your web browser and request /songs/T (or any other letter). You should see something like the image below.

Uh oh. The default filter doesn’t seem to be working for the tracks which have a nil composer value. Yes, as I write this, the base Stencil project has a bug… but our code is correct. (Feel free to implement a workaround for this if you wish; I leave that as an exercise for the reader as well. And yes, “exercises for the reader” are often “lazinesses for the author” in thin disguise.)

What about that {% empty %} part in our template? Well, the Chinook database actually has songs with titles that start with every letter in the alphabet, so even if you go to “/songs/X” or “/songs/Z” you’ll still get a table full of songs. But we can do tricky things to see how the {% empty %} bit would work here. Try going to “/songs/-” (that’s a hyphen) and see what happens; since there are no song titles that begin with a hyphen, you’ll see the “There are no songs that begin with -.” message where the table rows were before. So that works!